Troops of the West Indies Regiment in camp on the Albert-Amiens Road, September 1916

Photo: © Imperial War Museum

African, Caribbean, and Asian demobilised soldiers from the Colonies and mariners working in the British Merchant Navy, settled in Canning Town in the 1920s and 1930s, where they worked for a better future, some marrying locally-born working-class women and raising families with limited means.

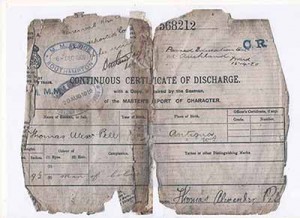

Thomas Pell from Antigua, worked as a seaman on British ships and later settled in Canning Town. Harold Brown was born in Poplar in London in 1899. He served in the 3/4th Battalion and 6th Battalion Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. He received commendation cards for ‘distinguishing himself in the field’ from the Commanding Officer of his Division on two occasions and was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry in 1918. After the First World War he went to sea with the Royal Mail for two years and then worked at the Royal Albert Docks until his death in 1955.

Coloured seamen were discharged with little money, with slim hopes of further employment, and no means to pay for their return passage.

Free Churches set up their own organisations to minister to seamen.

- The Destitute Sailors’ Asylum, established in 1827 in Dock Street in a converted warehouse, provided food for shipwrecked and destitute seamen.

- The Sailors’ Home, was founded in 1835 in Well Street.

- The Strangers’ Home in West India Dock Road opened in 1857, and was also known as the Home for Asiatics, Africans, South Sea Islanders and Others.

- The Queen Victoria Seamen’s Rest in Jeremiah Street, around the corner from East India Dock Road, was founded in the 1890s as the Seamen’s Mission of the Wesleyan Methodist Church and provided accommodation, educational and recreational facilities.

- The Methodist Pastor of Indian origin, Kamal Chunchie, founded the Coloured Men’s Institute in Canning Town in 1926 in order to help distribute food, clothing and other items to non-white seamen, their families and the wider Black community in the port. It was housed in a former Chinese lodging house at 13-25 Tidal Basin.

The Flying Angel building dates from 1936. It was built as a Seamen’s Mission. At that time, the surrounding docks would have been thriving. The mission closed in 1973 and the building was then used as a college. It has now been converted to flats. The building is known as the Flying Angel because of a sculpture of an angel on a balcony above the main entrance doorway.

Between 1919 and 1921, fierce competition for jobs, and in particular seafaring jobs, ignited the hostility of white seamen against Caribbean, African and Asian seamen, and sparked riots in London, Liverpool and Cardiff.

White seamen’s unions pressurised the government to legislate against the employment of ‘coloured aliens‘. This resulted in the Aliens Order of 1920, and the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order of 1925.

‘Coloured’ seamen (African, Caribbean and Asian), who did not hold documentation to prove their status as British subjects, were required to register at a police station as ‘alien’ and therefore be subjected to repatriation.

At the ports of hire, sailors were not required to hold passports, and if they did these were often confiscated to be investigated in Britain. Unlike white mariners, their discharge certificates did not constitute proof of their nationality, due to allegations of trafficking in these papers.

As a result, many African, Indian, and West Indian seamen with British citizenship were arbitrarily registered as aliens until proof to the contrary. The status carried the threat of repatriation, for not being qualified to apply for employment or financial support. Ship masters were very reluctant to employ them or to take them back.

Complaints from coloured seamen led to the issuing of identity cards via the Empire Colonial Offices, to posters and articles in the colonies’ local papers, alerting mariners of the necessity of obtaining a card as proof of identity, prior to sailing for the United Kingdom.

Residents lived in the numerous rows of terraced housing that sprang up in the area, built for the workers of the local factories and docks. Flats were scarce and as workers could not afford the rent of a whole house, these ‘two up, two downs’ often accommodated two or more families, with one family per floor in a make-shift ‘flat’.

A two up-two down house in Bidder Street, Canning Town.

Photo © Newham Archives and Local Studies Library

Each flat consisted of a living room/work room and a bedroom. These were usually complemented by a scullery with a cold water tap. The ground floor and first floor tenants usually shared a toilet at the back of the house, known as the privy.

Speculative builders with little experience or capital built and managed the houses. Poor materials and faulty building techniques compromised the quality of the dwellings. Walls had to be buttressed to prevent them from falling down, plaster crumbled to reveal the brickwork beneath, and windows and door frames were skewed. As Lotte Tendler remembers:

“We managed. It wasn’t an easy life. Always lived in furnished rooms with utility furniture. You used to get two blankets when you got married and utility coupons: two sheets, a bag, a mattress and you could buy on your coupons a table, chairs and a sideboard.”

High unemployment and precarious working conditions led to resourceful ways of paying the high rents. For example, rent parties were organised whereby friends and neighbours would contribute to the collection for the rent whilst having a good time eating, drinking and playing the piano.

Wages were limited so people became resourceful and creative in order to make their limited means go as far as possible. Second-hand clothing was found at Rathbone Market. The Docks also provided access to cheap cloth brought in from around the Empire. Local tailors then skilfully cut and sewed them into gowns.

Local shops such as the haberdashery store in Prince Regent Lane, the hairdressers and Gregory’s the Pawnbrokers in Victoria Dock Road catered for the needs of their customers, who were able to purchase parcelled quantities of goods ‘on tick’ (on credit) over time, to suit their pockets.

The butchers sold cheaper cuts such as pigs’ heads, pigs’ trotters, spare ribs and stuffed hearts. People also enjoyed pie and mash, bread and dripping and sugar sandwiches. There was also the occasional treat and Murkoff vanilla ice creams in particular are still a vivid memory of local residents.

H. Murkoff’s ice cream shop in Canning Town, famous for its vanilla ice cream.

Photo © Stan Dyson’s Collection

Finances were tightly balanced such that it was not unusual for clothes, jewellery, suits and china to be handed in at the pawn shop on a Monday and then reclaimed once wages were paid on a Thursday.

Although life in Canning Town was often tough, there were good times too. Religion played a very important role in the life of the community. West Ham Central Mission and St. Luke’s Church – the ‘Cathedral of the East End’ – witnessed many marriages, baptisms and funeral services. Both are still viewed as hubs of the community who shared very happy moments within their walls.

There were many activities to be enjoyed during residents’ leisure time too, from motorbike and greyhound racing to boxing and, of course, football. West Ham Stadium, which was situated in Prince Regent Lane at that time, played host to a range of sporting events. Dog racing used to take place there every Wednesday and Friday, with crowds of up to 56,000 in its heyday. The stadium also hosted Speedway events, the first of which took place on Saturday 28th July 1928. Organised by Dirt-Track Speedways Ltd, the event saw the leading British, Australian and American speedway riders entertain audiences with formidable displays of motor racing.

When the stadium was not hosting dog or motorcycle races, it was full of football fans cheering and shouting for their favourite teams. In 1935, Jack Leslie, born to a Jamaican father and a local-born woman in Canning Town, led the Fairburn House Old Boys against West Ham United. Leslie was the only professional black player in England during his time with Plymouth Argyle. Despite being a prodigy, the colour of his skin prevented him from playing for England.

Boxing clubs fostered discipline in working class boys and aimed at deflecting them from the lures of street life. Boxing matches were packed and enjoyed within the community. One resident remembers:

“My Grandfather, Bill Taylor, started the Marina Boxing Club in 1934. The club was in two old warehouses which were in the large yard behind his houses in Trinity Street. You had to walk through some big gates at the side of 2 Trinity Street to get into the yard where the club was.

Inside the first warehouse, about 300 people could be seated around the boxing ring. My grandfather bought the seats from an old cinema or music hall, in Borough High Street, that had just closed down. They were metal lift- up seats that screwed to the floor and were upholstered in red velvet.”

As well as sports, there were other, more gentle, pursuits to be had. Bird enthusiasts could, as now, enjoy the wildlife and tranquillity of Wanstead Flats. The Beckton Lido, opened in 1957, was also very popular, as were trips on the Woolwich Ferry. Locals could also catch a film, such as “Sanders Rivers” and “Song of Freedom” at the Imperial Palace. They may even have recognised themselves on screen as people from Draughtboard Alley were recruited as film extras at Teddington Studios in West London.

The West Ham Municipal Lido at Beckton Road, pictured in 1937.

Photo © Newham Archives and Local Studies Library

Tea parties provided the best occasion for ‘sweet encounters’. At the Coloured Men’s Institute, Pastor Kamal Chunchie held tea, Christmas and New Year Parties and concerts where classic and jazz music was played. Cheerful audiences joined in popular songs such as ‘Knees up Mother Brown’, ‘Roll out the Barrel’ at the music halls and dance halls lining Barking Road, where ‘tip tap’ dancers drew inspiration from the local national star – Josie Wood. Josie, a celebrated dancer, choreographer and dance teacher, was born in Canning Town to a merchant navy quartermaster from Dominica surnamed Wood who married a locally born woman.

Seaside outings to Southend provided opportunities to breathe the fresh marine air, leaving behind the noxious though familiar fumes from the Beckton gas plants, the chemical factories, the Thames Iron works, the Tate & Lyle plants, the glass works and the rubber works (India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Cable Company).